Merle coat pattern testing is included in the Embark for Breeders DNA Kits by testing for the M Locus. Merle coat pattern is common to several dog breeds, including the Australian Shepherd, Catahoula Leopard Dog, and Shetland Sheepdog, among many others. In Dachshunds, this color pattern is known as “dapple.”

A tricolor merle Australian Shepherd.

What is merle at the genetic level?

Merle arises from a mutation in the pigment gene PMEL (we’ll call this mutation “M*” going forward). M* disrupts PMEL expression, leading to mottled or patchy coat pattern. Dogs with the “M*m” genotype are likely to appear merle or phantom merle. This is when the dog is not obviously merle patterned but has a merle allele; dogs with the “M*M*” genotype are likely to appear merle or double merle. Dogs with the “mm” genotype are unlikely to appear merle.

What’s with the * in M*?

This has to do with the nature of the M* mutation itself. M* is actually a specific type of transposable element (a “jumping gene,” a vestige of a retrotransposable viral element) known as a SINE. This SINE has jumped right into a gene involved in coat pigmentation called PMEL, thereby disrupting its function (as described in Clark et al, 2006). This is not uncommon–many dog diseases and coat color patterns arise from SINE insertions, such as the saddle tan coat pattern, centronuclear myopathy in Labrador Retrievers, and early retinal degeneration in Norwegian Elkhounds.

What is uncommon about M* is that it can, and does, mutate rapidly in a single generation or even across a cell division. This means that a phenotypical merle dog can produce puppies with different lengthed merle alleles. A merle dog could also have several merle alleles–these dogs would be called mosaics. And the length of the merle allele determines the coat pattern of the dog.

Why length matters

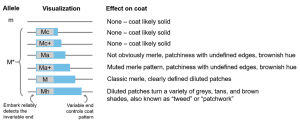

Below is a schematic of the different-lengthed M* alleles that were recently described in Langevin et al., 2018. From short to long, they are cryptic merle (Mc), atypical merle (Ma and Ma+), classic merle (M), and harlequin merle (Mh); we have also included the effect on coat that each allele confers.

Adapted from Langevin et al, 2018.

As you can see, only one end of the M* allele changes in length (the blue tail depicted above)–this end can and does affect the ultimate coat pattern of the dog. However, due to the nature of microarray-based technology, Embark only queries the invariable end–the end that doesn’t change. We can reliably detect the invariable end in every merle dog we’ve queried. However, if you want to make breeding decisions around merle, the length of the variable end matters.

Merle coat and breeding

Generally, when breeders apply merle testing as part of their breeding decisions, they’re worried about producing double merle dogs. Double merle dogs are dogs with two copies of the classic merle (M) allele. These dogs are often dramatically depigmented and can have significant visual and hearing impairment. Due to its adverse effects on quality of life, producing dogs with this genotype is discouraged. A double merle dog will test “M*M*” with Embark.

However, a dog can have tested “M*M*” on our Embark array and have an unusual coat pattern, which some might call “minimal merle.” This is almost certainly due to mosaicism leading to just a segment of the coat being that patchy merle pattern. A dog like this has no issue seeing or hearing. They could certainly be used in a breeding program, but Mc+ and Ma dogs should not be bred to M dogs as there is a risk of producing a double merle.

If you have questions, please reach out to us at [email protected]. Interested in getting started? Check out the Embark for Breeders DNA kits.